From the Eiffel Tower to the Washington Monument, everyone has a different architectural standard in their heads—that piece that makes you go, “Wow.” There’s so much more that goes into those building decisions than just how to physically construct something, though. Rebecca Ferlotti, content marketer, sat down with Melanie Domzalski, RGI’s architectural designer, to talk about how designers can more effectively incorporate psychology into built environments.

What, exactly, does an architectural designer do?

Really, it’s a term used in lieu of “architect.” It’s comparable, but there are legalities around calling yourself an architect.

In order to become an architect, you have to first get a degree from an accredited university. You have to have supervised hours with a licensed architect. And you also have to pass a series of exams. If you don’t fulfill those three requirements, you can’t call yourself an architect—legally.

I got my degree and fulfilled nearly all of my hours, but I didn’t go through the exam process, so I’m not licensed. I have a deep understanding of architecture, but I can only call myself an architectural designer. That said, I’m able to bring that knowledge of designing the spaces we live in (and what goes into all of that).

Speaking of design, what are some of the basic components you find yourself incorporating into each of your designs?

It really depends on the project, who the users are, and what the client needs. It’s all on a case-by-case basis.

But my approach to design in general is to consider what the human experience would be like within an environment. For example, biophilic design elements—or incorporating natural elements into my designs—is something that’s important to me because it supports human wellness. It goes back to supporting the user, whether it’s a home, workspace, or otherwise.

Thinking about urban environments, residential environments, work environments, and anything RGI is building, what are the similarities and differences between each sect of design?

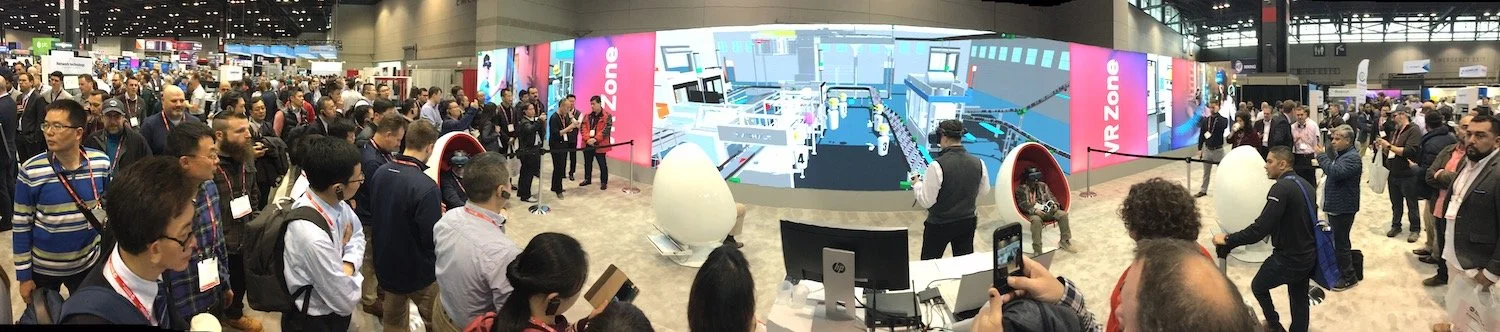

Since I have a psychology background, I initially went into urban design, which was a good fit for a while. I had to consider the overall environment and wayfinding: how to get from place to place. The obvious difference between urban environments and what I do at RGI is scale. But while a trade show booth might be smaller than a skyscraper, the approach is still the same. For me, it’s looking at the existing conditions, understanding the users’ needs, and figuring out how the client’s needs fit into that.

I’m always gathering information—observing, listening, researching, conceptualizing. And thinking about what the build is even going to look like. Do I want someone to see this place or should it be more private? What’s the circulation? What do you want to be near a certain person and what do you not want to be near? With elevation, what do you see when you’re looking at a built environment from the side?

With elevation, a big part of that is accessibility as well. And part of that human-centered design approach you’ve been telling us about is seeing all different types of accessibility in action. You’ve traveled around a bit because your brother is in the army. How do you think travel has influenced your design approach?

I can do all the research and listen to all the people, but that’s influenced by my perspective and my interpretation of what people need. So when you travel, you get to experience environments firsthand. Different cultures influence how you perceive things and how you understand environments. People get excited about the Eiffel Tower, but you can’t see why they’re excited about it until you get there. It’s a grand thing. I’ve actually never seen the Eiffel Tower, so I can’t say anything about that experience. But it’s taking into consideration why a monument is monumental.

It’s a different approach in Europe. Many cities over there are older. In the U.S., we have distinct urban areas and suburbs. Suburbs were created because of the automobile—for people to get away from “dirty cities.” And with the introduction of the car, suburbs could be placed farther out. In Europe, the cities are dense. You can walk through them. You’re going to have a different experience walking through a place and seeing people’s faces than you would if you’re driving. When I’m driving, I’m not looking at the person next to me. I’m jamming out. So another part of travel is understanding what it’s like to be outside that typical zone and reflecting on what you see.

There’s a lot of depth to travel; and when you do anything, you’re imposing yourself to an extent. You have a certain world view, but then that can evolve and change the more you learn and the more experiences you have. Traveling is about gaining knowledge and experience. Anything you do in life is based on what knowledge and experience you have, so it just broadens it.

Also too, when you go see something in person—whether it be the Eiffel Tower or another monument—being able to see how different people are experiencing those environments is super helpful to take back with you. You start to consider how we can replicate that buzz locally.

Exactly! Yes, it’s my experience, but I’m also seeing other people’s reactions. So it’s like you also get that chance at observation. I was at the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago recently. We were in this narrow hallway, and then we walked out into this big room where there was a life-sized submarine. I thought it was so cool. And then behind me, I heard a child audibly say, “Wow!” It reminded me it wasn’t just a solo experience. I got to see people’s reactions and how they engaged with the experience in front of them.

You can learn so much by observing people. People watching is so fascinating.

And people watching is part of your job, so you can definitely use that as an excuse! Getting out there and seeing these built environments is helpful for designers, but so is the act of being outside. There’s that ease of getting from place to place we talked about within European cities. You’re a huge advocate for mental health awareness and incorporating mental health into your designs, and being outdoors is one facet of that. What are some of the other ways effective design can aid mental health?

With mental health, it starts at awareness. It’s understanding what mental health conditions exist outside of you and also within you. When you have the awareness, you’re gaining education around it. Some people don’t know that exercise really does improve your mental health. I personally have depression, and I remember during my first therapy appointment, she told me that a natural way to produce serotonin is moving your body intentionally.

Since my first degree is in psychology, I wanted to understand how psychology related to architecture, since there’s not as much information out there. But one of the places there is some research is within healthcare settings. For example, there are studies about patient rooms without windows. It took longer for patients to heal without a window than it did when they had a window. The study quantifiably showed that access to nature and views of the outdoors shortened recovery time. Along those same lines, in residential buildings, every bedroom has to have a window. It shows you how important access to nature is because it will affect your health if you don’t have that.

I used to work with children at a residential treatment center for youth experiencing severe mental health issues. When I noticed the children were starting to get tense, the first thing I thought about was the environment. What’s the temperature? What’s the lighting like? I was always considering how their immediate environment could help them feel better.

If you’re a designer or someone who’s just trying to be more aware of how environments are affecting your users, incorporate those biophilic elements. Live plants are best, but if you’re like me and can’t keep plants alive, then get fake plants! Give yourself and your users access to natural elements and pay attention to how it makes everyone feel.

Research is also huge. It’s not designing a space to impose your egocentric perspective. Sally Augustin wrote this amazing book called Place Advantage: Applied Psychology for Interior Architecture. She talks about the universal features of a well-designed space:

Complying – Create a space that supports the necessary tasks.

Communicating – The space should align with who you are and who the user is.

Comforting – Develop a space that reduces stress.

Challenging – A built environment should help us grow and develop as people.

Continuing – Places should be flexible and have the ability to evolve over time.

The human brain is so complex, so it’s really about continuing to learn and test out strategies to see what works.

And you’ve studied the brain extensively. You did an independent study on the psychology of architecture. What were your main takeaways that you still enact?

It ties back to what I said earlier about the challenge of figuring out how psychology and architecture can even have that relationship. It isn’t a well-known thing, so I had to create my own courses. The more we can talk about it, the more designers can be better at implementing these concepts and growing awareness.

My first independent study looked at an overall relationship of psychology and architecture. And my second looked at creating supportive environments for domestic abuse survivors. As a whole, one of my main takeaways was how people experience environments from a holistic perspective. And how someone behaves in one environment can drastically change within a different environment. There’s both internal and external factors for that—nature and nurture.

It’s a really big task to take on to pay attention to all these aspects, to make informed decisions to support users. You want to create environments that are accessible to as many people as possible, which goes back to universal design.

I want this information to be easy to get a hold of because it’s so important. We’re all humans going through this experience on this tiny little rock in a big ol’ universe. Learning helps us better support each other. And designing spaces informed by psychology is a part of that.